Oil Market Forecast - June 2021

Summary

In this edition of our Oil Market Forecast we focus on the IEA’s recent Net Zero by 2050 report. We also look at the continued recovery in oil demand and another recent jump in oil prices and how this feeds in to our medium term supply and demand forecast. US onshore activity has yet to show a response to the recent rise in oil prices and there is still no consensus as to whether and to what degree US activity will recover.

A few key points:

- Our assessment of the IEA’s roadmap concludes that it fails to provide a credible path to Net Zero by 2050, primarily because of the extent of its reliance on new technology.

- Our view is that the IEA’s roadmap was constructed in this way to make recommendations more acceptable to the signatories of the Paris Agreement, by downplaying the extent of the behavioral changes required to transition from fossil fuels.

- Given the response to the report over the last few weeks, this attempt appears to have been unsuccessful, with several G7 nations pushing back publicly on the report’s key recommendations. This sets the stage for a very contentious COP 26.

- We see the report as tacit admission by the IEA that the objectives of the Paris climate agreement are not achievable.

- Oil demand growth forecasts have been consistently robust for the second half of the year.

- We expect global crude storage to fall back to its long term average by the end of the year.

- Brent and WTI spot prices continue to rise with both benchmarks passing $70 / bbl this month.

- The IEA and EIA both predict a rebound in US oil production in 2022 as higher prices stimulate US onshore activity.

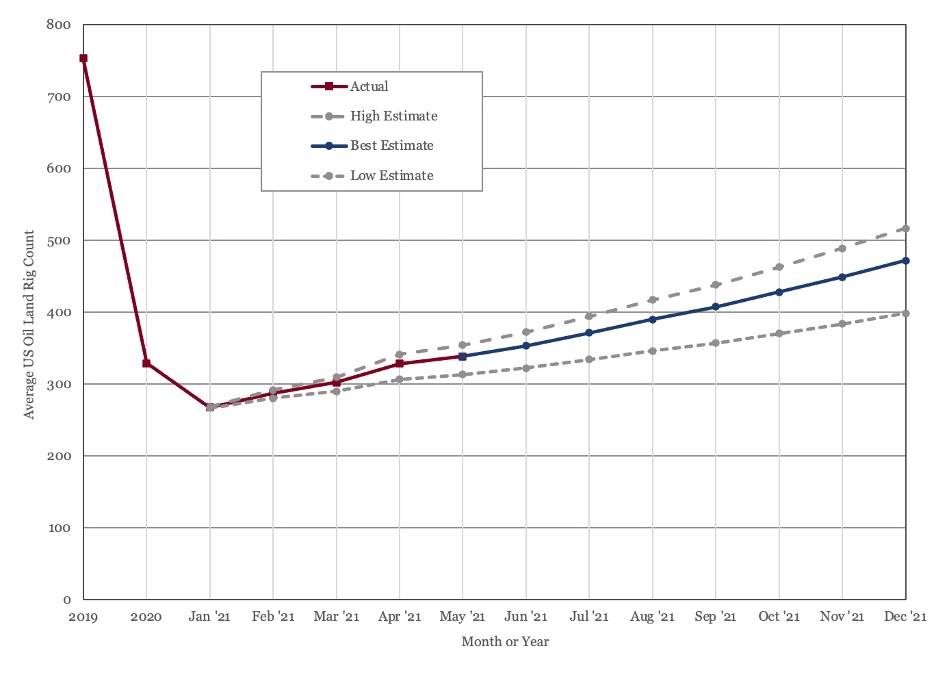

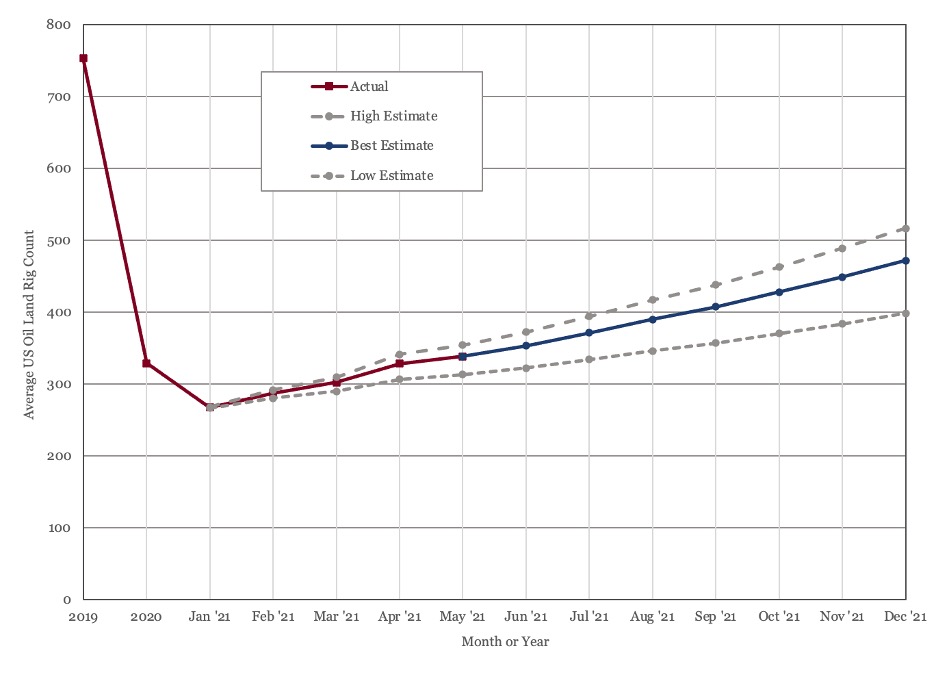

- US rig count continues to grow but shows no sign of acceleration, our own forecast sees a decline in US oil production next year.

“Net Zero by 2050”

Last month saw the International Energy Agency (IEA) published its climate roadmap – “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” (1); a publication that has generated much discussion in the last few weeks. Over the next few pages, we will look at what the roadmap is, and what it isn’t, why the IEA published it, and what it means.

What is “Net Zero by 2050”?

The IEA is best known for its forecasting of energy supply and demand balance and the first point that must be made is that “Net Zero by 2050” is not a forecast, it is a roadmap. Rather than a predication of what the IEA thinks will happen in the future, it is a guide to the things that need to happen in a world that conforms to a carbon budget consistent with a temperature increase of 1.5 ºC over pre-industrial levels, which is the target enshrined in the Paris Agreement. The IEA makes this point clear in the report itself, presenting three scenarios – STEPS, APC and NZE. STEPS is the IEA’s stated policies scenario; this is what they forecast will happen based on current national policies. APC is the announced pledges scenario, which includes all outstanding national pledges, in addition to current national policies. NZE is the Net Zero by 2050 scenario, which outlines the actions required to limit climate change to 1.5ºC over pre-industrial levels.

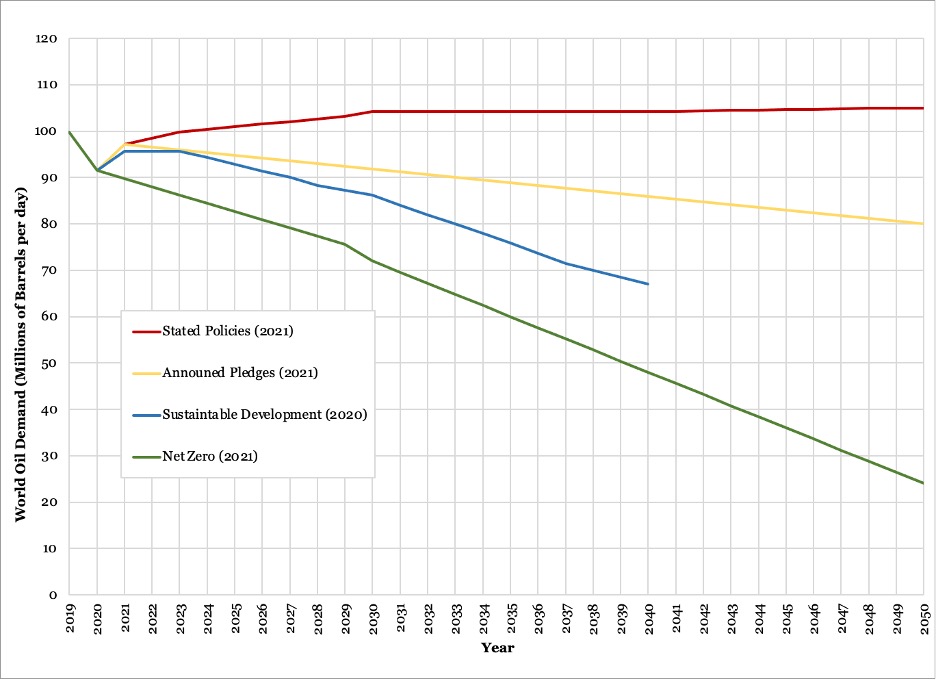

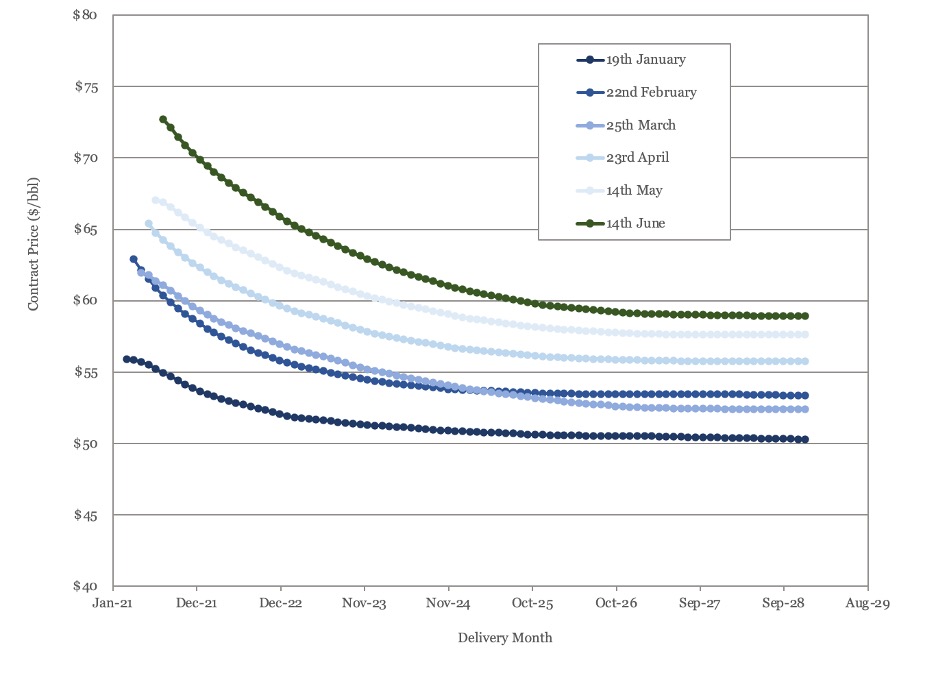

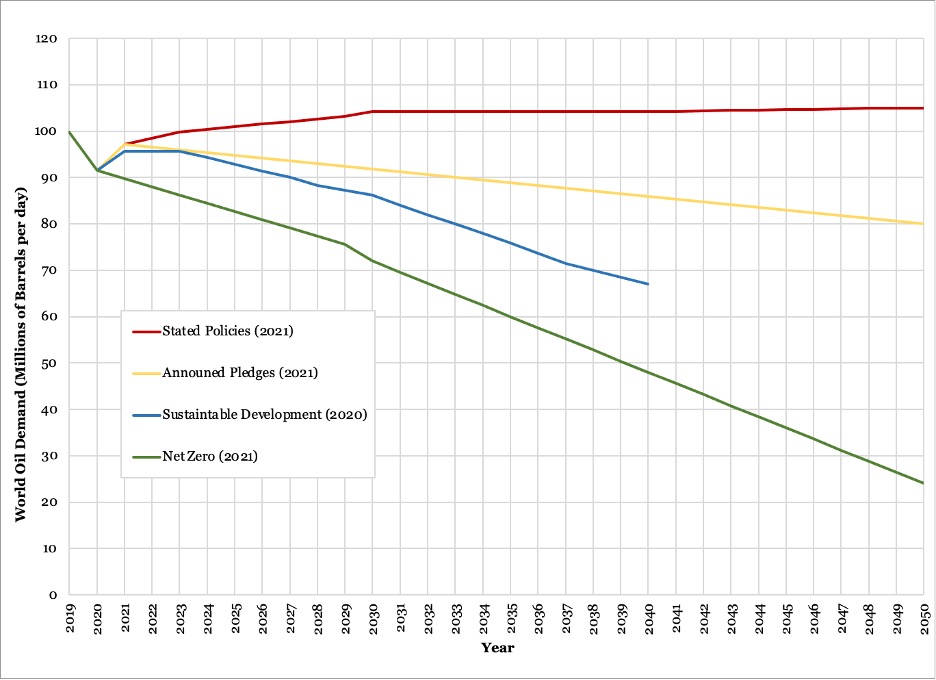

The IEA has historically published three scenarios in its annual flagship World Energy Outlook report – Stated Policies, Net Zero by 2050 and the Sustainable Development Scenario which limits warming to 1.8ºC above pre-industrial levels and does not rely on negative emissions. Sustainable Development appears to have been dropped from the latest publication in favor of the APC scenario. The impact on oil demand under each of these four scenarios is shown in Figure 1, below. STEPS, APC and NZE are taken from the Net Zero by 2050 report, while the Sustainable Development case is taken from last year’s World Energy Outlook (2).

Figure 1 - Oil Demand under IEA Scenarios

The IEA’s approach of presenting multiple scenarios has been a useful guide, as it has shown the gap between current polices and what would actually be required to satisfy the limits of the Paris Agreement. What the IEA does in its latest publication is to take this one step further and spell out, sector by sector and year by year, the policy and behavioral changes that are required to meet this target. If Figure 1 gives some indication of the gap between target and reality, the latest IEA report is sobering to say the least.

Why did the IEA publish “Net Zero by 2050”?

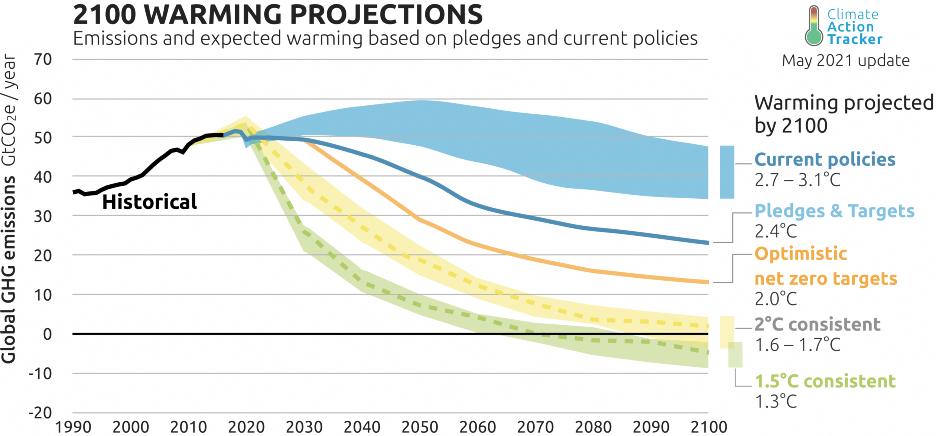

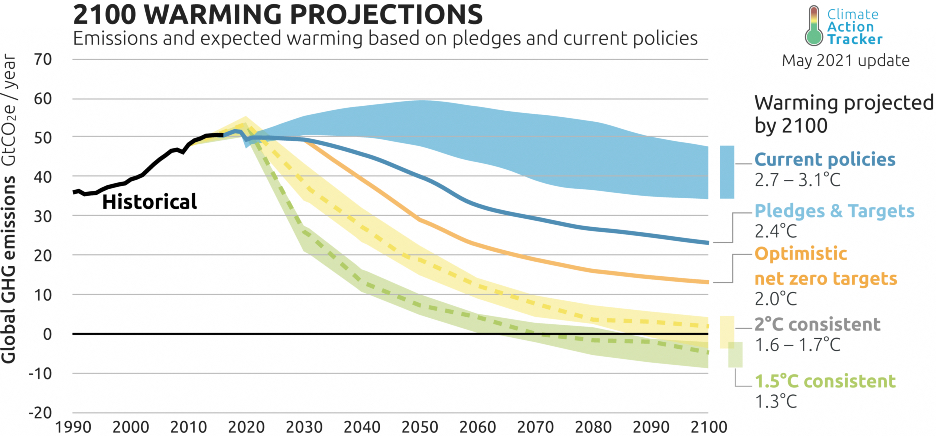

It is worth spending a couple of paragraphs going over the basis for the IEA Net Zero roadmap, the Paris Agreement and how these link to national efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions. We will start by trying to map the IEA scenarios to climate change predictions. Figure 2, below (Copyright 2021 Climate Action Tracker by Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute) shows projected temperature increase for a range of scenarios that can be linked to the IEA scenarios. These forecasts are based on the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) MAGIC model.

Figure 2 - Temperature Increase above Pre-Industrial Levels

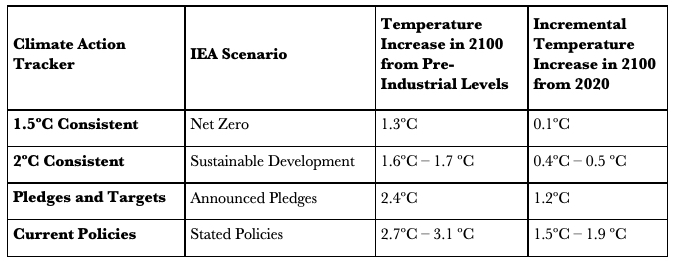

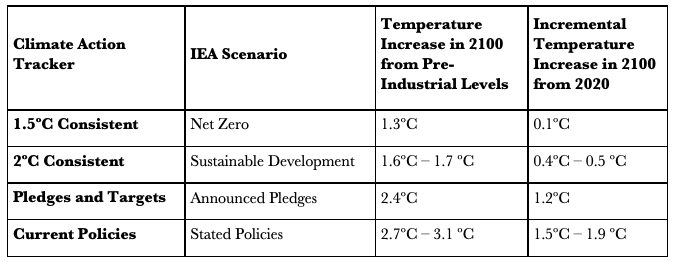

The warming estimates provided are above pre-industrial levels. Current temperature increase is estimated at being 1.2ºC above pre-industrial levels (3). In Table 1, we have attempted to map the Climate Action Tracker and IEA scenarios to show incremental temperate increase for a given IEA scenario.

Table 1 - Climate Action Tracker and IEA Scenario Mapping

The Paris Agreement is a treaty on climate change that was adopted in at the Conference of Parties (COP) 21 in Paris in 2015. The COP is the highest decision making body of the United Nations Framework Agreement on Climate Change. The objective of the treaty is to limit global temperature increases to well below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels and aim to limit it to 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels. Referring to Table 1, either Net Zero or Sustainable Development would satisfy this requirement, the other IEA scenarios would not.

The Paris Agreement is often presented as legally binding commitment to limit climate change, which is true to a degree. Under the Paris Agreement, each signatory must submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) on a five yearly cycle and each NDC should be more stringent than the last. This procedural component is legally binding. However, there is no provision for countries to set a specific target by a specific date, or any sanction if they fail to comply with their NDC’s (4).

This brings us back to the purpose of the IEA’s latest report. The COP 26 is scheduled to take place this November in the UK, and it was the UK government who commissioned the IEA’s report to “inform the high-level negotiations that will take place...” (5). This explains the purpose of the report; to set the table for the COP 26 negotiation by providing a toolkit to assemble NDCs and eliminate any ambiguity on outcomes for a given set of measures.

Understood from this perspective, the report could be extremely valuable. If the IEA report is credible and if the measures outlined are technically, economically, and politically feasible then it should facilitate a productive COP 26 with participants committing to concrete, measurable, time based targets that would reliably limit global temperature increase. However, if those conditions are not satisfied, it could backfire badly. A poorly designed set of recommendations would lead the world in the wrong direction and no nation state will accept being publicly shamed into committing to politically impossible actions. In assessing the report, we will use these criteria – is the roadmap credible and will its proposals inspire a commitment to action by the COP 26 participants?

Is the Roadmap Credible?

The IEA was originally formed in the 1970’s with a mandate to co-ordinate the response to physical disruptions in the supply of oil and to compile and provide statistics on the international oil market. Since its inception, that mandate has morphed into broader mission to recommend policies that “enhance the reliability, affordability and sustainability of energy.”(6). This broader mission inevitably moves the IEA from its statistical roots into the public policy arena, from the technocratic to the political. “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” reflects this evolution, as it is a hybrid, a public policy platform built on a statistical base. Where the report is at its strongest is in the presentation of data, where it is more open to criticism is in its choices and emphasis.

First to choices. Building scenarios, as the IEA report acknowledges, requires the modeler to make choices, and choices are always subjective. In the IEA report, there are three choices that stand out - the first is the preference for renewables over nuclear in power generation, the second is the reliance on new technology and the third is assumptions around the behavioral change of citizens.

Nuclear is an established technology that reliably generates huge quantities of energy while emitting no carbon dioxide. It has none of the intermittency, energy density, physical footprint, or technology requirements of renewables. Nuclear is, however, deeply unpopular in many countries and with mainstream environmental groups. While the amount of electricity generated by nuclear nearly doubles between 2050, the amount of electricity generated by renewables increases 24 fold over the same period. The technocratic choice would have been to advocate for much more nuclear, as a proven if unpopular solution, instead the IEA chose to rely heavily on technologies that don’t currently exist.

About 15% of CO2 emissions savings through 2030 and fully 50% of CO2 emissions savings through 2050 are reliant on technologies that are currently under development. This choice has been, rightly, criticized on all sides. Over a 30 year period it may be reasonable to ascribe a small percentage to future technology, but at the scale deployed in the IEA roadmap, it is just a plug – the variable in the forecast that balances everything out. The scenario as presented is based on hope, and whole it is inspiring, hope is not a strategy. We can’t know why the IEA made this choice, but one reason may be choice number three, behavioral changes.

The IEA ascribes around 5% of emissions reductions to behavior changes, which the text does highlight – “For citizens the world over, the NZE brings profound changes, and their active support is essential if it is to succeed.” Without much more nuclear or new technology, behavioral change would have had to pick up the slack. We can only assume that the degree of behavioral change required in the absence of more nuclear or new technology would have clearly rendered the roadmap politically impossible. Whether the world’s citizens are willing to support the greatly reduced behavioral changes outlined by the IEA is questionable – as acknowledged by the IEA themselves:

“Much depends, for example, on the pace of innovation in new and emerging technologies, the extent to which citizens are able or willing to change behaviour, the availability of sustainable bioenergy and the extent and effectiveness of international collaboration.”

The choice of new technology also serves to support the most report’s most mendacious claim – that doing all of this is not just cost free but will make the world a richer place. It is, of course, easy to make such a claim when most of the heavy lifting is done by technology that does not currently exist, and so the costs of that technology can be as low as they need to be to support he desired conclusion. More credible, internationally recognized work has already established that the costs of conforming the temperature increases enshrined in the Paris Agreement far outweigh and potential benefits (7).

This brings us to emphasis. The IEA report made headlines, and won plaudits from many activists, for calling time on the oil & gas industry, when it stated that exploration and development of oil and gas should cease this year. The same message is highlighted throughout the report. The oil & gas industry is deeply unpopular with the general public and the investment community, especially and Europe and statements like that generate a lot of clicks, but the statement is both disingenuous and irresponsible.

It is disingenuous because the production of oil & gas is not very carbon intensive, rather it is the use of hydrocarbons as a fuel that releases carbon dioxide. If the message is that the world must stop using hydrocarbons, then the instruction to stop driving, flying, and heating your home should be delivered to the world’s citizens, not the handful of companies that supply them.

It is irresponsible because, while the statement may be true for the Net Zero scenario, it is far from true for the IEA Stated Policies scenario – the red line in Figure 1. That line is the IEA’s current forecast for oil demand, and it requires an enormous level of ongoing investment in exploration and development to maintain that supply. Maintenance of oil supply was the IEA’s original mandate and, under their current forecast, the statement that exploration and development should stop this year is, based on their own core function, false.

While a false choice was highlighted, a genuine reality was underplayed. Climate change is caused by everyone who has access to them using fossil fuels as they are intended; the only way to limit climate change is to stop using fossil fuels. Unfortunately, there are currently no substitutes that provide equivalent utility at equivalent cost. If there were, crafting NDCs would be a lot more straightforward. Forcing the world to abandon fossil fuels without having identified equivalent substitutes, means less energy at higher cost for everyone. Are people really willing to accept a substantially lower standard of living today, to limit the risk of temperature increases 80 years from now? The magic of new technology allows the IEA to underplay the impact of their roadmap on the daily lives of the world’s citizens and in doing so the IEA ducked the opportunity to have that discussion.

The report does not lay out a credible roadmap to meet the Paris Agreement. It also misses an opportunity to stimulate debate on a path forward and the real policies and tradeoffs required to limit climate change.

Commitment to Action

It’s been three weeks since the IEA report has been published and its receptions has been mixed. Environmental activists have welcomed it, while voicing concerns on the reliance on new technology. Unsurprisingly, it has received criticism from nations whose economies are heavily dependent on fossil fuels. One Russian spokesperson accused the IEA of having arrived at its findings ‘by using reverse calculations’, while another said ‘In my view this a simplistic approach. It is also unrealistic’, both sentiments we would agree with. Saudi Arabia’s Energy Minister was more direct in his criticism, reportedly saying “It is a sequel of the ‘La La Land’ movie. Why should I take it seriously?” (8).

Of more concern was the broader international reception (9). Japan, Australia, and Norway disputed the findings. Japanese minister Hiroshi Kajiyama said, “It’s a fact that there are sections the Japanese government does not agree with,”, in reference to recommendations on halting new fossil fuel investment and phasing out coal. Australia resources minister Keith Pitt said “Coal, oil and gas will continue to be a big part of Australia’s energy mix”. Norway’s’ oil minister, Tina Bru, said that it would not “make a difference from a global perspective” if Norway stopped producing oil and gas. Norway confirmed that it intends to continue to license new acreage for exploration.

The UK minister responsible for COP 26 welcomed the report but intended to continue to move forward with new fossil fuel licensing. The response from the United States was similar, with the White House climate advisor Gina McCarthy saying that changes would be gradual and that fossil fuel projects would continue. John Kerry, the US climate envoy, focused on the need to explore new technologies (10).

The consensus seems to be that the IEA report lacks widespread support, with criticism leveled at both the underlying analysis and a reluctance to adopt its recommendations setting the stage for an adversarial dynamic at the COP 26. If the G7 nations, including the COP 26 hosts, are already publicly signaling their unwillingness to adopt some of the main recommendations, then there is little hope that emerging economies will feel any pressure to do so. The IEA report appears to have failed, and failed badly, in creating any form of commitment to action.

Where does this leave us?

The IEA report fails on both counts – it does not provide a credible roadmap to limit climate change, but the roadmap provides is still too extreme for adoption by signatories to the Paris Agreement. A more credible roadmap would have relied mainly on proven technology and behavioral change, enforced by regulation, with some small allowance for technology – a lot more nuclear, more expensive energy and a lower standard of living for all the worlds citizens. This is the message a technocratic organization should have delivered. These measures would not have been adopted either, but at least it could have formed the basis for a dialog on how to move forward.

The “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” serves as a tacit admission, in direct contradiction to the assertion in its opening paragraph, that a path still exists to Paris climate agreements target of limiting temperature rise to 1. 5ºC.

As we move from the roadmap to the current outlook for oil supply and demand in our next section, we see that the IEA are now forecasting an acceleration in oil demand.

Oil Supply and Demand

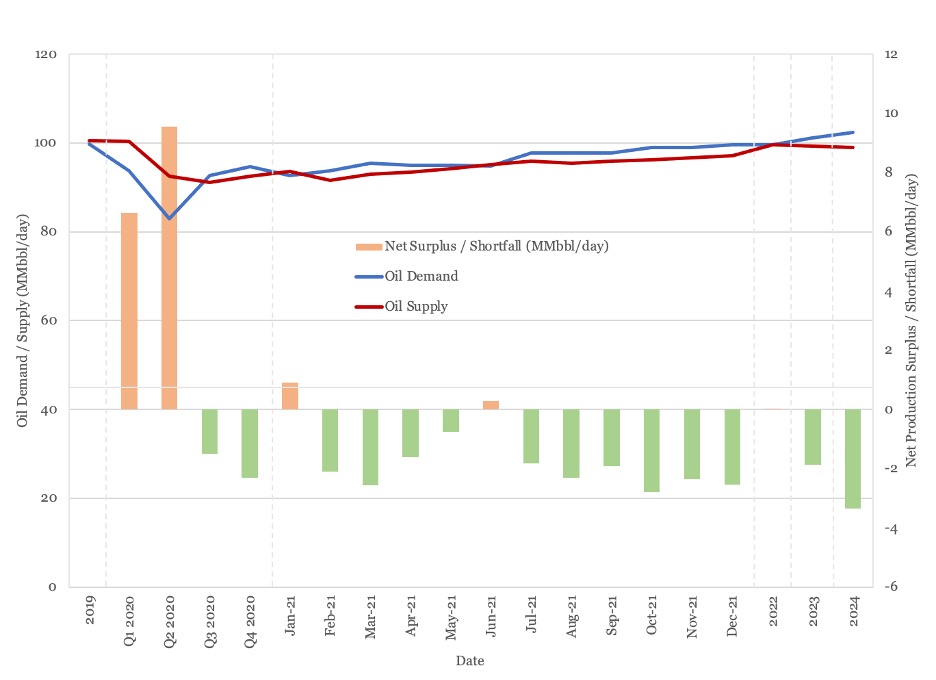

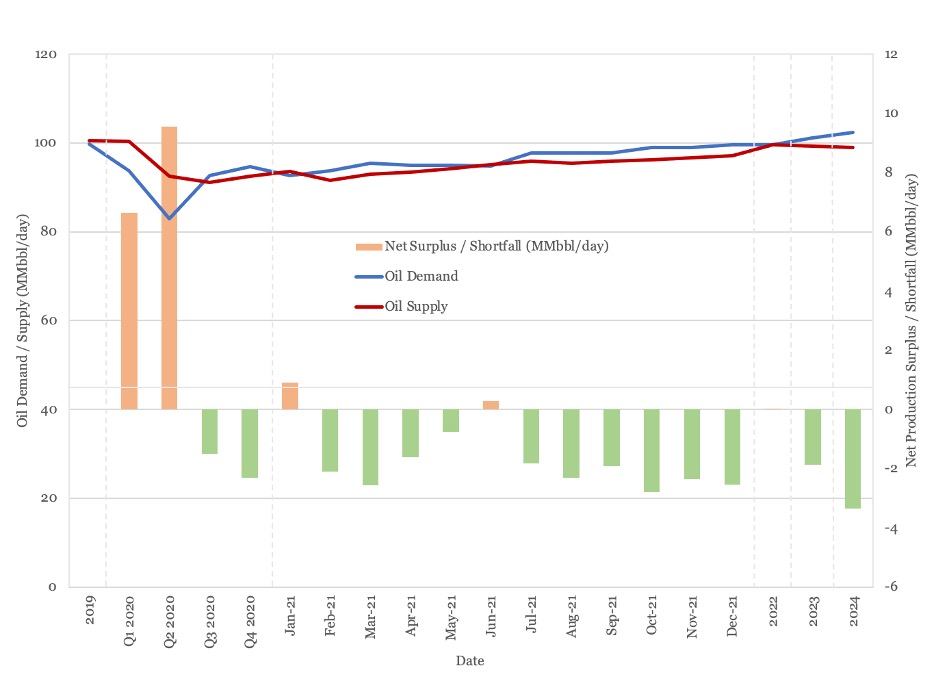

We estimate that global oil supply increased by over 800,000 bbl/day in May from April, to 94.2 MMbbl/day. OPEC reaffirmed their plan to gradually return production to the market at their 17th OPEC and non OPEC ministerial meeting on 1st of June (11). This agreement details production levels through July 2021, with an additional 450,000 bbl/day being returned to market this month. We expect a small supply surplus in June, with the market then returning to deficit for the rest of the year.

The first look at February supply data shows that US production fell sharply, from 16.3 MMbbl/day in January to 15.0 MMbbl/day, as a result of the impact of winter storm Uri. US supply is expected to have recovered by March.

Oil demand is still expected to jump sharply, by nearly 3 MMbbl/day between Q2 and Q3 this year as economies recover and people return to work and start traveling again. In their latest forecast (12), the IEA expects oil demand to exceed pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2022, rather than 2023, due to a faster than expected recovery.

Our oil supply and demand forecast is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - Supply and Demand Surplus Forecast

Oil Storage

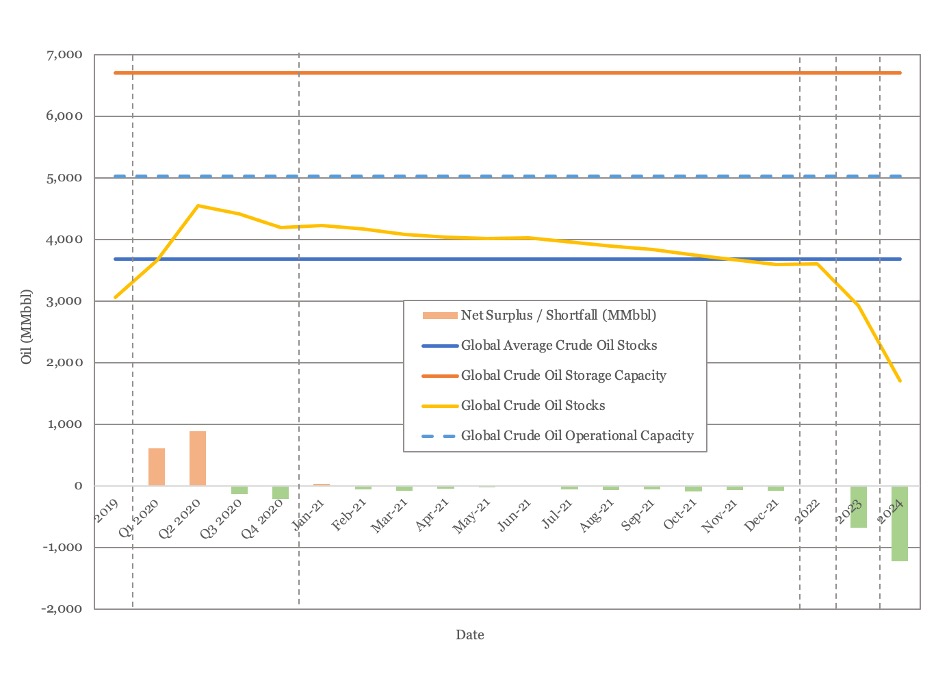

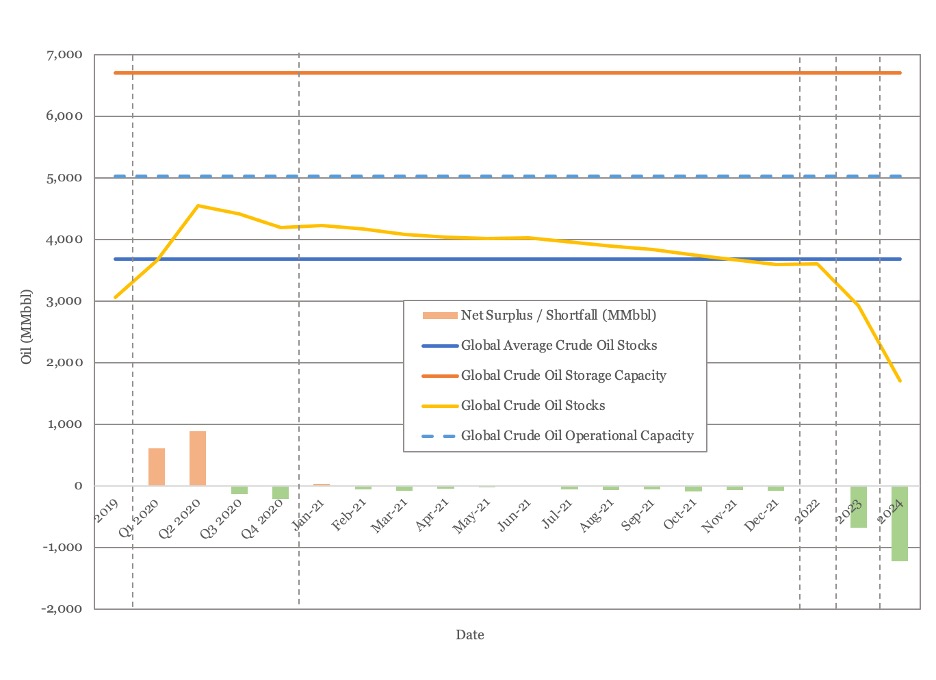

In their latest report, the IEA noted that OECD stocks have fallen below their 2015 – 2019 pre-COVID average levels for the first time. The IEA shows a market in deficit for the remainder of the year, as does our own model. We estimate global oil inventory drawdowns of 176 million barrels and 426 million barrels in the first and second halves of 2021 respectively.

Both the IEA and EIA (13) predict that oil demand will continue to strengthen through 2022 and both are predicting a rebound in US supply next year on the back of sustained higher oil prices. The IEA view is that the US will add back 900,000 bbl/day of production in 2022. This, together with OPEC+ spare capacity, returning Iranian supply, and some other OECD additions from Canada and Norway provide plenty of cushion for oil markets in 2022. The EIA, in their latest forecast, has nearly 2022 US production at nearly 1.2 MMbbl/day after falling this year, while acknowledging that the relationship between oil price and the US supply response seems to have weakened. A recovery of that magnitude would set a new US production record in 2022.

Both the IEA and EIA forecasts are predicated on strengthening oil prices driving a rebound in US shale oil production. Our own forecast has US production falling by a further 600,000 bbl/day next year, as we don’t see current rig activity levels as sufficient to maintain production and have yet to see any indication of a faster recovery in rig activity.

Figure 4 shows global storage capacity and inventories. If supply and demand continue to evolve as currently forecast, we think global inventories should return to long term average around the third fourth quarter of this year and stay around that level through 2022. Beyond 2022, they are set to decline significantly in the absence of new investment.

Figure 4 - Global Storage Chart

Oil Prices

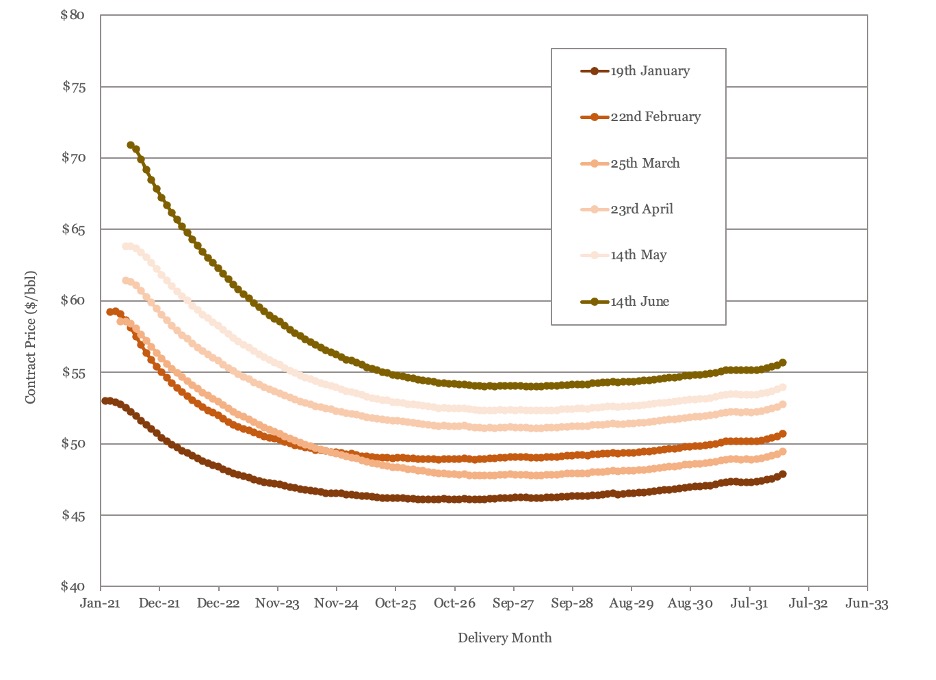

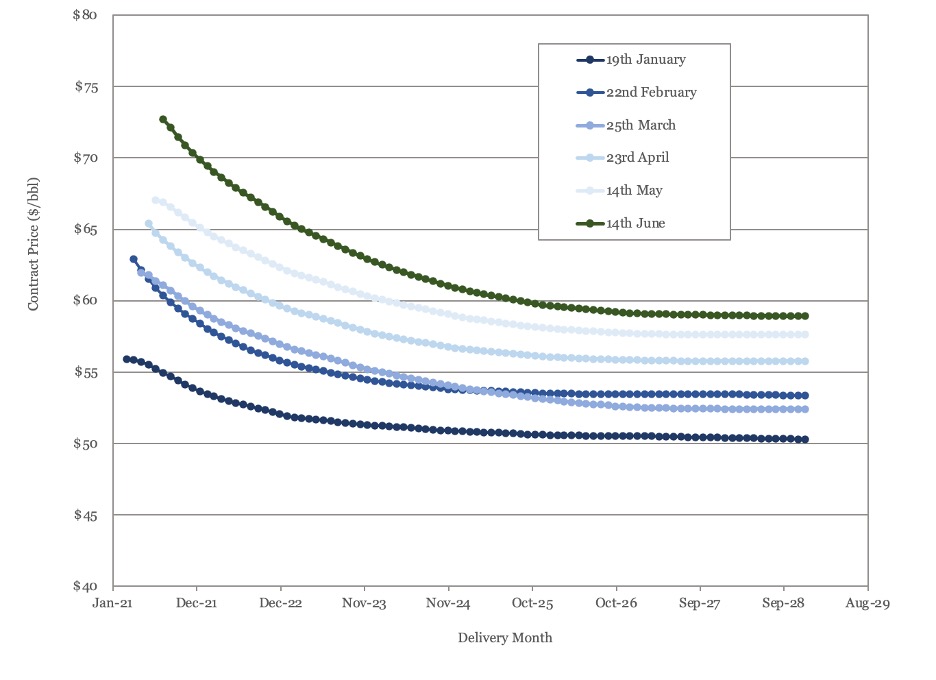

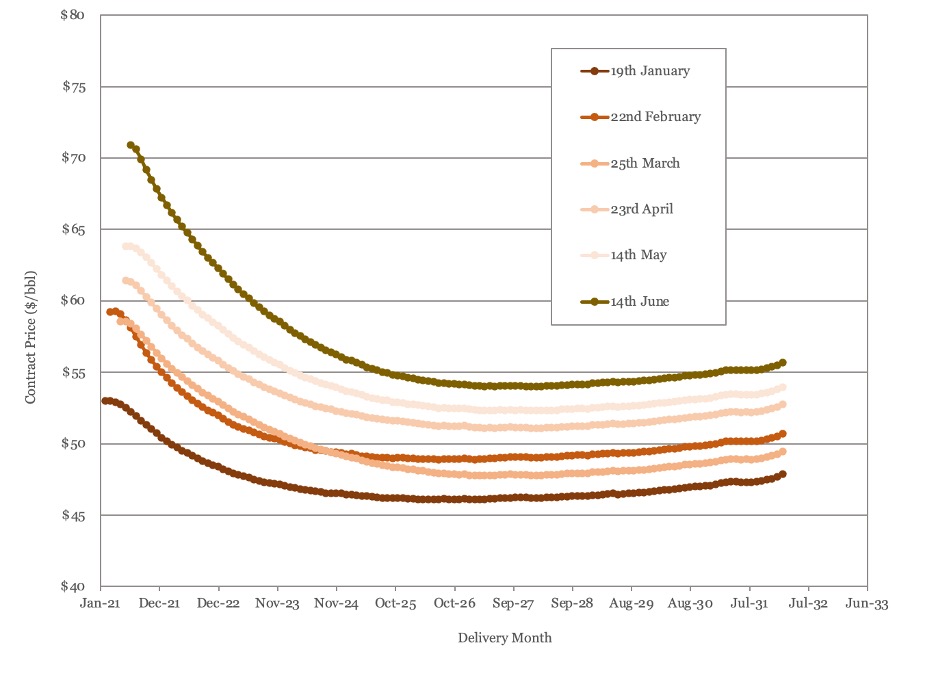

Both WTI and Brent passed $70 per barrel earlier this month and both futures curves have shown sharp increases over the near term. Brent futures are now above $70/barrel through the end of this year and above $60 out to 2024, while WTI futures are above $60/barrel out to June 2023.

Figure 5 - Brent Crude Oil Futures

Figure 6 - WTI Crude Oil Futures

US Activity

US land oil rig counts continued to climb in through May and into June, rising from 337 on the 14th of May to 352 on the 11th of June. The rate of rig count growth remains steady, with no sign of an acceleration in rate of increase of activity. Historic and forecast rig counts are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7 - US Land Oil Rig Count

(1) “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector”, May 2021, International Energy Agency

(2) World Energy Outlook 2020, October 2020, International Energy Agency

(3) The CAT Thermometer, Climate Action Tracker, https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-thermometer/

(4) "The Legal Character of the Paris Agreement", Bodansky, Daniel (2016), Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law.

(5) “Pathway to critical and formidable goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 is narrow but brings huge benefits, according to IEA special report”, Press Release, 18th May 2021, International Energy Agency.

(6) https://www.iea.org/about/mission

(7) “Projections and Uncertainties about climate change in an era of minimal climate policies”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 22933, William D. Nordhaus, September 2017.

(8) “Russia and Saudi Arabia reject calls to end oil and gas spending”, 4th June 2021, CNBC

(9) “Member countries push back against IEA’s net zero road map”, May 23rd, 2021, Financial Times

(10) “IEA’s urgent fossil fuel warning earns mixed reception from producers”, May 26th, 2021, Reuters

(11) OPEC Press Release No 12/2021, Vienna, Austria, 1st June 2021

(12) Oil Market Report – May 2021, International Energy Agency

(13) Short Term Energy Outlook (STEO), June 8th, 2021, U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Oil Market Forecast - June 2021

Summary

In this edition of our Oil Market Forecast we focus on the IEA’s recent Net Zero by 2050 report. We also look at the continued recovery in oil demand and another recent jump in oil prices and how this feeds in to our medium term supply and demand forecast. US onshore activity has yet to show a response to the recent rise in oil prices and there is still no consensus as to whether and to what degree US activity will recover.

A few key points:

- Our assessment of the IEA’s roadmap concludes that it fails to provide a credible path to Net Zero by 2050, primarily because of the extent of its reliance on new technology.

- Our view is that the IEA’s roadmap was constructed in this way to make recommendations more acceptable to the signatories of the Paris Agreement, by downplaying the extent of the behavioral changes required to transition from fossil fuels.

- Given the response to the report over the last few weeks, this attempt appears to have been unsuccessful, with several G7 nations pushing back publicly on the report’s key recommendations. This sets the stage for a very contentious COP 26.

- We see the report as tacit admission by the IEA that the objectives of the Paris climate agreement are not achievable.

- Oil demand growth forecasts have been consistently robust for the second half of the year.

- We expect global crude storage to fall back to its long term average by the end of the year.

- Brent and WTI spot prices continue to rise with both benchmarks passing $70 / bbl this month.

- The IEA and EIA both predict a rebound in US oil production in 2022 as higher prices stimulate US onshore activity.

- US rig count continues to grow but shows no sign of acceleration, our own forecast sees a decline in US oil production next year.

“Net Zero by 2050”

Last month saw the International Energy Agency (IEA) published its climate roadmap – “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” (1); a publication that has generated much discussion in the last few weeks. Over the next few pages, we will look at what the roadmap is, and what it isn’t, why the IEA published it, and what it means.

What is “Net Zero by 2050”?

The IEA is best known for its forecasting of energy supply and demand balance and the first point that must be made is that “Net Zero by 2050” is not a forecast, it is a roadmap. Rather than a predication of what the IEA thinks will happen in the future, it is a guide to the things that need to happen in a world that conforms to a carbon budget consistent with a temperature increase of 1.5 ºC over pre-industrial levels, which is the target enshrined in the Paris Agreement. The IEA makes this point clear in the report itself, presenting three scenarios – STEPS, APC and NZE. STEPS is the IEA’s stated policies scenario; this is what they forecast will happen based on current national policies. APC is the announced pledges scenario, which includes all outstanding national pledges, in addition to current national policies. NZE is the Net Zero by 2050 scenario, which outlines the actions required to limit climate change to 1.5ºC over pre-industrial levels.

The IEA has historically published three scenarios in its annual flagship World Energy Outlook report – Stated Policies, Net Zero by 2050 and the Sustainable Development Scenario which limits warming to 1.8ºC above pre-industrial levels and does not rely on negative emissions. Sustainable Development appears to have been dropped from the latest publication in favor of the APC scenario. The impact on oil demand under each of these four scenarios is shown in Figure 1, below. STEPS, APC and NZE are taken from the Net Zero by 2050 report, while the Sustainable Development case is taken from last year’s World Energy Outlook (2).

Figure 1 - Oil Demand under IEA Scenarios

The IEA’s approach of presenting multiple scenarios has been a useful guide, as it has shown the gap between current polices and what would actually be required to satisfy the limits of the Paris Agreement. What the IEA does in its latest publication is to take this one step further and spell out, sector by sector and year by year, the policy and behavioral changes that are required to meet this target. If Figure 1 gives some indication of the gap between target and reality, the latest IEA report is sobering to say the least.

Why did the IEA publish “Net Zero by 2050”?

It is worth spending a couple of paragraphs going over the basis for the IEA Net Zero roadmap, the Paris Agreement and how these link to national efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions. We will start by trying to map the IEA scenarios to climate change predictions. Figure 2, below (Copyright 2021 Climate Action Tracker by Climate Analytics and NewClimate Institute) shows projected temperature increase for a range of scenarios that can be linked to the IEA scenarios. These forecasts are based on the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) MAGIC model.

Figure 2 - Temperature Increase above Pre-Industrial Levels

The warming estimates provided are above pre-industrial levels. Current temperature increase is estimated at being 1.2ºC above pre-industrial levels (3). In Table 1, we have attempted to map the Climate Action Tracker and IEA scenarios to show incremental temperate increase for a given IEA scenario.

Table 1 - Climate Action Tracker and IEA Scenario Mapping

The Paris Agreement is a treaty on climate change that was adopted in at the Conference of Parties (COP) 21 in Paris in 2015. The COP is the highest decision making body of the United Nations Framework Agreement on Climate Change. The objective of the treaty is to limit global temperature increases to well below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels and aim to limit it to 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels. Referring to Table 1, either Net Zero or Sustainable Development would satisfy this requirement, the other IEA scenarios would not.

The Paris Agreement is often presented as legally binding commitment to limit climate change, which is true to a degree. Under the Paris Agreement, each signatory must submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) on a five yearly cycle and each NDC should be more stringent than the last. This procedural component is legally binding. However, there is no provision for countries to set a specific target by a specific date, or any sanction if they fail to comply with their NDC’s (4).

This brings us back to the purpose of the IEA’s latest report. The COP 26 is scheduled to take place this November in the UK, and it was the UK government who commissioned the IEA’s report to “inform the high-level negotiations that will take place...” (5). This explains the purpose of the report; to set the table for the COP 26 negotiation by providing a toolkit to assemble NDCs and eliminate any ambiguity on outcomes for a given set of measures.

Understood from this perspective, the report could be extremely valuable. If the IEA report is credible and if the measures outlined are technically, economically, and politically feasible then it should facilitate a productive COP 26 with participants committing to concrete, measurable, time based targets that would reliably limit global temperature increase. However, if those conditions are not satisfied, it could backfire badly. A poorly designed set of recommendations would lead the world in the wrong direction and no nation state will accept being publicly shamed into committing to politically impossible actions. In assessing the report, we will use these criteria – is the roadmap credible and will its proposals inspire a commitment to action by the COP 26 participants?

Is the Roadmap Credible?

The IEA was originally formed in the 1970’s with a mandate to co-ordinate the response to physical disruptions in the supply of oil and to compile and provide statistics on the international oil market. Since its inception, that mandate has morphed into broader mission to recommend policies that “enhance the reliability, affordability and sustainability of energy.”(6). This broader mission inevitably moves the IEA from its statistical roots into the public policy arena, from the technocratic to the political. “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” reflects this evolution, as it is a hybrid, a public policy platform built on a statistical base. Where the report is at its strongest is in the presentation of data, where it is more open to criticism is in its choices and emphasis.

First to choices. Building scenarios, as the IEA report acknowledges, requires the modeler to make choices, and choices are always subjective. In the IEA report, there are three choices that stand out - the first is the preference for renewables over nuclear in power generation, the second is the reliance on new technology and the third is assumptions around the behavioral change of citizens.

Nuclear is an established technology that reliably generates huge quantities of energy while emitting no carbon dioxide. It has none of the intermittency, energy density, physical footprint, or technology requirements of renewables. Nuclear is, however, deeply unpopular in many countries and with mainstream environmental groups. While the amount of electricity generated by nuclear nearly doubles between 2050, the amount of electricity generated by renewables increases 24 fold over the same period. The technocratic choice would have been to advocate for much more nuclear, as a proven if unpopular solution, instead the IEA chose to rely heavily on technologies that don’t currently exist.

About 15% of CO2 emissions savings through 2030 and fully 50% of CO2 emissions savings through 2050 are reliant on technologies that are currently under development. This choice has been, rightly, criticized on all sides. Over a 30 year period it may be reasonable to ascribe a small percentage to future technology, but at the scale deployed in the IEA roadmap, it is just a plug – the variable in the forecast that balances everything out. The scenario as presented is based on hope, and whole it is inspiring, hope is not a strategy. We can’t know why the IEA made this choice, but one reason may be choice number three, behavioral changes.

The IEA ascribes around 5% of emissions reductions to behavior changes, which the text does highlight – “For citizens the world over, the NZE brings profound changes, and their active support is essential if it is to succeed.” Without much more nuclear or new technology, behavioral change would have had to pick up the slack. We can only assume that the degree of behavioral change required in the absence of more nuclear or new technology would have clearly rendered the roadmap politically impossible. Whether the world’s citizens are willing to support the greatly reduced behavioral changes outlined by the IEA is questionable – as acknowledged by the IEA themselves:

“Much depends, for example, on the pace of innovation in new and emerging technologies, the extent to which citizens are able or willing to change behaviour, the availability of sustainable bioenergy and the extent and effectiveness of international collaboration.”

The choice of new technology also serves to support the most report’s most mendacious claim – that doing all of this is not just cost free but will make the world a richer place. It is, of course, easy to make such a claim when most of the heavy lifting is done by technology that does not currently exist, and so the costs of that technology can be as low as they need to be to support he desired conclusion. More credible, internationally recognized work has already established that the costs of conforming the temperature increases enshrined in the Paris Agreement far outweigh and potential benefits (7).

This brings us to emphasis. The IEA report made headlines, and won plaudits from many activists, for calling time on the oil & gas industry, when it stated that exploration and development of oil and gas should cease this year. The same message is highlighted throughout the report. The oil & gas industry is deeply unpopular with the general public and the investment community, especially and Europe and statements like that generate a lot of clicks, but the statement is both disingenuous and irresponsible.

It is disingenuous because the production of oil & gas is not very carbon intensive, rather it is the use of hydrocarbons as a fuel that releases carbon dioxide. If the message is that the world must stop using hydrocarbons, then the instruction to stop driving, flying, and heating your home should be delivered to the world’s citizens, not the handful of companies that supply them.

It is irresponsible because, while the statement may be true for the Net Zero scenario, it is far from true for the IEA Stated Policies scenario – the red line in Figure 1. That line is the IEA’s current forecast for oil demand, and it requires an enormous level of ongoing investment in exploration and development to maintain that supply. Maintenance of oil supply was the IEA’s original mandate and, under their current forecast, the statement that exploration and development should stop this year is, based on their own core function, false.

While a false choice was highlighted, a genuine reality was underplayed. Climate change is caused by everyone who has access to them using fossil fuels as they are intended; the only way to limit climate change is to stop using fossil fuels. Unfortunately, there are currently no substitutes that provide equivalent utility at equivalent cost. If there were, crafting NDCs would be a lot more straightforward. Forcing the world to abandon fossil fuels without having identified equivalent substitutes, means less energy at higher cost for everyone. Are people really willing to accept a substantially lower standard of living today, to limit the risk of temperature increases 80 years from now? The magic of new technology allows the IEA to underplay the impact of their roadmap on the daily lives of the world’s citizens and in doing so the IEA ducked the opportunity to have that discussion.

The report does not lay out a credible roadmap to meet the Paris Agreement. It also misses an opportunity to stimulate debate on a path forward and the real policies and tradeoffs required to limit climate change.

Commitment to Action

It’s been three weeks since the IEA report has been published and its receptions has been mixed. Environmental activists have welcomed it, while voicing concerns on the reliance on new technology. Unsurprisingly, it has received criticism from nations whose economies are heavily dependent on fossil fuels. One Russian spokesperson accused the IEA of having arrived at its findings ‘by using reverse calculations’, while another said ‘In my view this a simplistic approach. It is also unrealistic’, both sentiments we would agree with. Saudi Arabia’s Energy Minister was more direct in his criticism, reportedly saying “It is a sequel of the ‘La La Land’ movie. Why should I take it seriously?” (8).

Of more concern was the broader international reception (9). Japan, Australia, and Norway disputed the findings. Japanese minister Hiroshi Kajiyama said, “It’s a fact that there are sections the Japanese government does not agree with,”, in reference to recommendations on halting new fossil fuel investment and phasing out coal. Australia resources minister Keith Pitt said “Coal, oil and gas will continue to be a big part of Australia’s energy mix”. Norway’s’ oil minister, Tina Bru, said that it would not “make a difference from a global perspective” if Norway stopped producing oil and gas. Norway confirmed that it intends to continue to license new acreage for exploration.

The UK minister responsible for COP 26 welcomed the report but intended to continue to move forward with new fossil fuel licensing. The response from the United States was similar, with the White House climate advisor Gina McCarthy saying that changes would be gradual and that fossil fuel projects would continue. John Kerry, the US climate envoy, focused on the need to explore new technologies (10).

The consensus seems to be that the IEA report lacks widespread support, with criticism leveled at both the underlying analysis and a reluctance to adopt its recommendations setting the stage for an adversarial dynamic at the COP 26. If the G7 nations, including the COP 26 hosts, are already publicly signaling their unwillingness to adopt some of the main recommendations, then there is little hope that emerging economies will feel any pressure to do so. The IEA report appears to have failed, and failed badly, in creating any form of commitment to action.

Where does this leave us?

The IEA report fails on both counts – it does not provide a credible roadmap to limit climate change, but the roadmap provides is still too extreme for adoption by signatories to the Paris Agreement. A more credible roadmap would have relied mainly on proven technology and behavioral change, enforced by regulation, with some small allowance for technology – a lot more nuclear, more expensive energy and a lower standard of living for all the worlds citizens. This is the message a technocratic organization should have delivered. These measures would not have been adopted either, but at least it could have formed the basis for a dialog on how to move forward.

The “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” serves as a tacit admission, in direct contradiction to the assertion in its opening paragraph, that a path still exists to Paris climate agreements target of limiting temperature rise to 1. 5ºC.

As we move from the roadmap to the current outlook for oil supply and demand in our next section, we see that the IEA are now forecasting an acceleration in oil demand.

Oil Supply and Demand

We estimate that global oil supply increased by over 800,000 bbl/day in May from April, to 94.2 MMbbl/day. OPEC reaffirmed their plan to gradually return production to the market at their 17th OPEC and non OPEC ministerial meeting on 1st of June (11). This agreement details production levels through July 2021, with an additional 450,000 bbl/day being returned to market this month. We expect a small supply surplus in June, with the market then returning to deficit for the rest of the year.

The first look at February supply data shows that US production fell sharply, from 16.3 MMbbl/day in January to 15.0 MMbbl/day, as a result of the impact of winter storm Uri. US supply is expected to have recovered by March.

Oil demand is still expected to jump sharply, by nearly 3 MMbbl/day between Q2 and Q3 this year as economies recover and people return to work and start traveling again. In their latest forecast (12), the IEA expects oil demand to exceed pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2022, rather than 2023, due to a faster than expected recovery.

Our oil supply and demand forecast is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - Supply and Demand Surplus Forecast

Oil Storage

In their latest report, the IEA noted that OECD stocks have fallen below their 2015 – 2019 pre-COVID average levels for the first time. The IEA shows a market in deficit for the remainder of the year, as does our own model. We estimate global oil inventory drawdowns of 176 million barrels and 426 million barrels in the first and second halves of 2021 respectively.

Both the IEA and EIA (13) predict that oil demand will continue to strengthen through 2022 and both are predicting a rebound in US supply next year on the back of sustained higher oil prices. The IEA view is that the US will add back 900,000 bbl/day of production in 2022. This, together with OPEC+ spare capacity, returning Iranian supply, and some other OECD additions from Canada and Norway provide plenty of cushion for oil markets in 2022. The EIA, in their latest forecast, has nearly 2022 US production at nearly 1.2 MMbbl/day after falling this year, while acknowledging that the relationship between oil price and the US supply response seems to have weakened. A recovery of that magnitude would set a new US production record in 2022.

Both the IEA and EIA forecasts are predicated on strengthening oil prices driving a rebound in US shale oil production. Our own forecast has US production falling by a further 600,000 bbl/day next year, as we don’t see current rig activity levels as sufficient to maintain production and have yet to see any indication of a faster recovery in rig activity.

Figure 4 shows global storage capacity and inventories. If supply and demand continue to evolve as currently forecast, we think global inventories should return to long term average around the third fourth quarter of this year and stay around that level through 2022. Beyond 2022, they are set to decline significantly in the absence of new investment.

Figure 4 - Global Storage Chart

Oil Prices

Both WTI and Brent passed $70 per barrel earlier this month and both futures curves have shown sharp increases over the near term. Brent futures are now above $70/barrel through the end of this year and above $60 out to 2024, while WTI futures are above $60/barrel out to June 2023.

Figure 5 - Brent Crude Oil Futures

Figure 6 - WTI Crude Oil Futures

US Activity

US land oil rig counts continued to climb in through May and into June, rising from 337 on the 14th of May to 352 on the 11th of June. The rate of rig count growth remains steady, with no sign of an acceleration in rate of increase of activity. Historic and forecast rig counts are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7 - US Land Oil Rig Count

(1) “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector”, May 2021, International Energy Agency

(2) World Energy Outlook 2020, October 2020, International Energy Agency

(3) The CAT Thermometer, Climate Action Tracker, https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-thermometer/

(4) "The Legal Character of the Paris Agreement", Bodansky, Daniel (2016), Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law.

(5) “Pathway to critical and formidable goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 is narrow but brings huge benefits, according to IEA special report”, Press Release, 18th May 2021, International Energy Agency.

(6) https://www.iea.org/about/mission

(7) “Projections and Uncertainties about climate change in an era of minimal climate policies”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 22933, William D. Nordhaus, September 2017.

(8) “Russia and Saudi Arabia reject calls to end oil and gas spending”, 4th June 2021, CNBC

(9) “Member countries push back against IEA’s net zero road map”, May 23rd, 2021, Financial Times

(10) “IEA’s urgent fossil fuel warning earns mixed reception from producers”, May 26th, 2021, Reuters

(11) OPEC Press Release No 12/2021, Vienna, Austria, 1st June 2021

(12) Oil Market Report – May 2021, International Energy Agency

(13) Short Term Energy Outlook (STEO), June 8th, 2021, U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Explore Our Services

Business Development

Oil & Gas an extractive industry, participants must continuously find and develop new oil & gas fields as existing fields decline, making business development a continuous process.

Strategy

We approach strategy through a scenario driven assessment of the client’s current portfolio, organizational competencies, and financial framework. The strategy defines portfolio actions and coveted asset attributes.